- Home

- Jojo Moyes

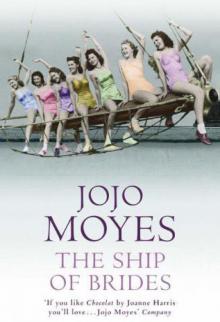

Ship of Brides Page 43

Ship of Brides Read online

Page 43

And suddenly there it was. Spoken twice before she heard it: ‘O’Brien, Mrs Margaret . . . Mrs O’Brien?’

‘Come on, girl,’ said a neighbour, shoving her to the front. ‘Shake a leg. It’s time to get off.’

The captain had just begun to show the Lord Mayor round the bridge when an officer appeared at the door. ‘Bride to see you, sir.’

The mayor, a pudding-shaped man whose chain of office hung from his sloping shoulders like a hammock, had shown an almost irresistible urge to touch everything. ‘Come to say their last goodbyes, eh?’ he remarked.

‘Show her in.’

Highfield thought he had probably known even before he saw her who it would be. She stood in the doorway, flushing as she saw the company he was in. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said, faltering. ‘I didn’t mean to interrupt.’

The mayor’s attention was on the dials in front of him, his fingers creeping towards them.

‘XO, look after the Mayor for a moment, would you?’ Ignoring Dobson’s glare, he walked over to the doorway. She was dressed in a pale blue short-sleeved blouse and khaki trousers, her hair pinned at the back of her head. She looked exhausted, and unutterably sad.

‘I just wanted to say goodbye and check that there was nothing else you wanted me to do. I mean, that everything is okay.’

‘All fine,’ he said, glancing down at his leg. ‘I think we can say you’re dismissed now, Sister Mackenzie.’

She gazed down at the dockside below them, teeming with people.

‘Will you be all right?’ he asked.

‘I’ll be fine, Captain.’

‘I don’t doubt it.’ He realised he wanted to say more to this quiet, enigmatic woman. He wanted to talk to her again, to hear more about her time in service, to have her explain the circumstances of her marriage. He had friends in high places: he wanted to ensure that she would find a good job. That her skills would not be wasted. There was no guarantee, after all, that any of these girls would be appreciated.

But in front of his men, he could say nothing. Nothing that would be considered appropriate, anyway.

She stepped forward and they shook hands, the captain acutely conscious of the other men’s curious glances. ‘Thank you . . . for everything,’ he said quietly.

‘The pleasure was all mine, sir. Just glad to have been able to help.’

‘If there is ever . . . any way, in which I might help you, I’d be delighted if you would allow me . . .’

She smiled at him, the sadness briefly lifting from her eyes, and then, with a shake of her head, which told him he could not be the answer, she was gone.

Margaret stood in front of her husband, stunned briefly into muteness by the immutable fact of him. The sheer handsomeness of him in his civilian clothes. The redness of his hair. The broad, spatulate tips of his fingers. The way he was staring at her belly. She pushed back a strand of hair and wished suddenly that she had made the effort to set it. She tried to speak, then found she did not know what to say.

Joe looked at her for what seemed an eternity. She was shocked at how unfamiliar he appeared, here, in this strange place. As if this new environment had made him alien. Self-consciousness made her look down. Panicked and curiously ashamed, she felt paralysed. Then he stepped forward with a huge grin. ‘Bloody hell, woman, you look like a whale.’ He threw his arms round her, saying her name over and over, hugging her so tightly that the baby kicked in protest, which made him jump back in surprise.

‘Would you credit that, Mother? A kick like a mule, she said, and she wasn’t wrong. How about that?’ He rested his hand on her belly, then took hers. He gazed into her face. ‘Ah, Jesus, Maggie, it’s good to see you.’

He enclosed her in his arms again, then reluctantly released her, and Margaret found herself clinging to his hand, as if it were a lifeline in this new country. It was then that she saw the woman standing with him, a couple of steps back, a headscarf tied round her head, her handbag clutched under her bosom as if she did not want to interfere. As Margaret attempted self-consciously to straighten her too-tight dress, all fingers and thumbs, the woman stepped forward, a smile breaking over her face. ‘Margaret, dear. I’m so glad to meet you. Look at you – you must be exhausted.’

There was the briefest pause and then, as Margaret struggled for words, Mrs O’Brien stepped forward to fold her into her chest. ‘How brave you are,’ she said into her hair. ‘All this way . . . away from your family . . . Well, don’t you worry. We’ll look after you now. You hear me? We’re all going to get along grand.’

She felt those hands patting her back, smelt the faint, maternal smell of lavender, rosewater and baking. Margaret did not know who was more surprised, she or Joe, when she burst into tears.

The marine captain grabbed him as he was trying the door to the infirmary. Nicol pulled away from the tight grip on his shoulder. ‘Where the bloody hell have you been, Marine?’ His face was furious.

‘I’ve been – I’ve been looking for someone, sir.’ Nicol had exhausted most of the ship: the only conceivable place remaining was the flight deck.

‘Look at the state of you! What the hell’s happened to you, man? Prod A, that’s what it was. All men on the flight deck. Not a bloody great hole where you should have been.’

‘I’m sorry, sir—’

‘Sorry? Sorry? What the bloody hell would happen if everyone decided not to turn up, eh? Look at you! You smell like a bloody brewery.’

From outside, he heard another dull cheer. Outside. He had to get outside on to the decks. There, he could check with one of the WSOs whether Frances had left the ship. For all he knew she might, at this very moment, be preparing to step off.

‘I’m shocked at you, Nicol. You of all people—’

‘I’m sorry, sir, I’ve got to go.’

The marine captain’s mouth dropped open. His eyes bulged. ‘Go? You’ve got to go?’

‘Urgent business, sir.’ And then he ducked under the man’s arm, the apoplectic voice still ringing in his ears as he took the steps three at a time.

Avice saw them before they saw her. She stood beneath the gun turret, her hat pinned tightly to her head so that it wouldn’t blow away, and watched the little group below. Her mother was wearing the hat with the huge turquoise feather in it. It looked curiously ostentatious among all the tweeds, dull browns and greys. Her father, his own hat wedged low on his brow as he preferred it, kept glancing around him. She knew who he was looking for. In the mêlée of naval uniforms, he would be wondering how on earth they would ever find him. She barely noticed her surroundings, the scenery behind the dockyard. What was the point when she knew now that she would not be staying?

‘Radley. Mrs Avice Radley.’

Avice took a deep breath, brushed the front of her jacket and made her way slowly to the bottom of the gangplank, her back as straight as that of a model, her chin held high as she tried to disguise the awkwardness in her walk.

‘There she is! There she is!’ She heard her mother’s squawk of excitement. ‘Avice, darling! Look! Look! We’re here!’

In front of her, where the gangplank met the dockside, a bride whom Avice recognised from the dressmaking lectures was ambushed at the bottom of the steps and swept into the arms of a soldier. She dropped her bag and the hat she had been holding in her left hand, and was locked to him for an interminable length of time, her hands clutching his hair, his face pressed to hers, as they occasionally broke off to touch noses and murmur each other’s name. Unable to get past them, Avice had to stand there, trapped on the gangplank, trying to look away as the couple were passionately reacquainted.

‘Avice!’ Her mother was bobbing up and down on the other side of them like a brightly coloured cork. ‘There she is, Wilf! Look at our girl!’

Finally, the soldier realised he was holding up the other brides, uttered a half-hearted apology, then swept his girl off to the side. You know how it is, he had grinned.

Oh, yes, Avice replied. I know how it is.

Her father moved forward and held her. ‘Your mother hasn’t stopped fretting since you left. Couldn’t bear the thought of you two on bad terms on opposite sides of the world. How’s that for devotion, eh, Princess?’

There was such love and pride on both their faces. Avice realised, with horror, that if they carried on her face would crumple.

Deanna stepped forward. She was wearing a new cerise suit. ‘Which one was the prostitute? Mummy nearly came out in hives when she got Mrs Carter’s letter.’

‘Where’s Ian?’ Her mother was peering into the faces of the men in naval uniform. ‘Do you think he’s brought his family?’

‘You’d better not have lost my shoes,’ said Deanna, under her breath. ‘I want them out of your case before you disappear.’

‘He won’t be here,’ Avice said.

‘He’s never been sent off already. I thought the men were going to be allowed to meet you!’ Her mother’s gloved hand pressed to her face. ‘Well, thank goodness we came, Wilf. Don’t you think?’

‘Is his family coming to meet you anyway? We’ve heard nothing from them.’ Her father took her arm. ‘I’ve brought them a wireless. Top of the range.’

Avice stopped, set her face as straight as she could. ‘He’s not coming, Dad. He’s never coming. There’s been . . . there’s been a change of plan.’

There was a short silence. Her father turned to her. Avice thought she might have heard a snort of delight from her sister. ‘What do you mean? You’re not telling me I’ve just spent four hundred dollars on flights when there’s no bloody celebration going to take place? Have you any idea how much this trip has cost—’

‘Wilf!’ Her mother turned back to her daughter. ‘Avice, darling—’

‘I’m not going to talk about it here, on a dockside full of people.’

Her parents exchanged a glance. Deanna was unable to disguise her pleasure at this unexpected turn of events. It was as if she were impressed by the scale of Avice’s personal catastrophe.

As the four of them stood on the quay, the crowds milling around them, a distant loud-hailer called for someone, please, to come to the harbourmaster’s office to reclaim a small child. She was wearing a red coat and said her name was Molly. They had no further information.

Avice stared back at the ship. A bride was running recklessly down the gangplank in high heels. When she reached the bottom she launched herself into the arms of an officer, who lifted her off the ground, twirling her round and round in his arms. She could see he was an officer from his uniform. She had always been good on uniforms. Don’t say anything else, Avice willed them, biting her lip. Don’t say one more word. Or I’m going to stand here and howl so loudly that the whole of Plymouth will be brought to a halt.

Her mother adjusted her hat, pulled her fur a little closer round her shoulders, then took Avice’s arm and tucked it into the crook of her own. Perhaps understanding, perhaps seeing something in her daughter’s expression, she chose not to look her full in the face. When she spoke, there was a faint but definite break in her voice. ‘Well, dear, when you’re ready we’ll have a little chat at the hotel.’ She began to walk. ‘It’s a very nice hotel, you know. Beautiful-sized rooms. We’ve got our own lounge area attached to the bedrooms and views all the way to Cornwall . . .’

Frances walked slowly down the gangplank, her suitcase in her right hand, the other trailing lightly down the handrail. She was, she thought, invisible in this crowd of cheering, embracing people. As she drew closer to the dockside, she saw faces she recognised from the past six weeks, wreathed in smiles, contorted in emotional tears, pressed in passion to their husbands and, just for a moment, she allowed herself to imagine what it would have been like to be one of those girls for whom there was an embrace at the end of the gangplank, for whom there was not one but several pairs of welcoming arms to claim her.

She kept walking. A new start, she told herself. That was what it was all about. I have made a new start.

‘Frances!’ She turned to see Margaret, her dress riding up over her plump knees as she waved wildly. Joe stood beside her, an arm round her shoulders. An older woman held her other arm. She had a kind face, not unlike Margaret’s own, which was now beaming and tear-stained.

Frances went towards her. Her steps felt surprisingly unsteady on dry land and she struggled to walk without lurching. The two women dropped their bags and embraced.

‘You weren’t going to go without my address, were you?’

Frances shook her head, sneaking a glance at the two proud people who had claimed Margaret as their own. On the ship she and Margaret had felt like equals; now, alone in a sea of families, she felt diminished.

Margaret took a pen from her husband and accepted a scrap of paper from her mother-in-law. She put pen to paper, paused and laughed. ‘What is it?’ she said.

He laughed too, then scribbled something on the paper, which Margaret placed in Frances’s hand. ‘As soon as you get settled, you write me with your address, you hear? My good friend Frances,’ she explained to the two of them. ‘She helped look after me. She’s a nurse.’

‘Pleased to meet you, Frances,’ said Joe, thrusting out a huge hand. ‘You come and see us. Whenever.’

Frances tried to return some of his warmth in her own grasp. The older woman nodded and smiled, then glanced at her watch. ‘Joseph, train,’ she mouthed.

Frances knew it was time to leave.

‘You take care now,’ Margaret said, squeezing her arm.

‘I’ll look forward to hearing how it all goes,’ said Frances, nodding at her belly.

‘It’ll be fine,’ Margaret said, with confidence.

Frances watched the three of them as they made their way to the dockyard gates, still chatting, arms linked, until people closed round her and she couldn’t see any more.

She took a deep breath, trying to dislodge the huge lump in her throat. It will be all right, she told herself. A fresh start.

At that point, she glanced back at the ship. There were men moving around, women still waving. She could see nothing, no one. I’m not ready, she thought. I don’t want to go. She stood, a thin woman jostled by the crowds, tears streaming down her face.

Nicol pushed his way to the front of the queue and several of the waiting women protested loudly. ‘Frances Mackenzie,’ he shouted at the WSO. ‘Where is she?’

The woman bristled. ‘Do you mind? My job is to sign these ladies off the ship.’

He grabbed her, his voice hoarse with urgency. ‘Where is she?’

They stared at each other. Then her eyes narrowed and she ran her pen down several pages. ‘Mackenzie, you say. Mackie . . . Mackenzie, B. . . . Mackenzie, F. That it?’

He grabbed the clipboard.

‘She’s gone,’ she said, snatching it back. ‘She’s already disembarked. Now, if you’ll excuse me.’

Nicol ran to the side of the ship and leant over the rail, trying to see her in the crowd, trying to make out the distinctive, strong, slim frame, the pale reddish hair. Below him thousands of people were still on the side, jostling, weaving past each other, disappearing and reappearing.

His heart lodged somewhere high in his throat, and, in despair, he began to shout, ‘Frances, Frances,’ already grasping the scale of his loss, his defeat.

His voice, roughened with emotion, hovered for a moment over the crowds, caught, and then sailed away on the wind, back out to sea.

Captain Highfield was almost the last man to leave the ship. He had undergone his ceremonial goodbye, flanked by his men, but at the gangplank, he stood, looking out, as if reluctant to disembark. When they realised he was in no hurry to move, a number of senior officers had filed past, wishing him well in his future life. Dobson made his goodbye as brief as possible, and talked ostentatiously of his next posting. Duxbury departed arm in

arm with one of the brides. Rennick, who stayed longest, declined to look him in the eye, but enclosed his hand firmly within his own and told him in a tremulous voice ‘to take a little care after yourself’.

The captain laid a hand on his shoulder and pressed something into his palm.

And then he was alone, standing at the top of the gangplank.

Those few who were watching from the dockside, the few who were minded to pay him any attention, given the more pressing matters they had to attend to, remarked afterwards that it was strange to see a captain all by himself on such an occasion when there were so many crowds below. And that, strange as it might sound, they had rarely seen a grown man look more lost.

26

It was the last time I ever saw her. There were so many people, screaming and yelling and pushing to get to each other, and it was impossible to see. And I looked up, and someone was pulling at my arm and then a couple ran towards each other and just locked on to each other right in front of me and kissed and kissed, and I don’t think they could even hear me when I asked them to get out of the way. I couldn’t see. I couldn’t see a thing.

And I think it was then that I realised it was a lost cause. It was all lost. Because I could have stood there for a day and a night and hung on for ever but sometimes you just have to put one foot in front of the other and move on.

So that was what I did.

And that was the last I saw of her.

PART THREE

27

It seems so sad that I left so many wonderful mates, and never heard about them from that day to this . . . one met so many people during the war in times of great comradeship. Most people who recall those days admit to making the same mistake of not keeping in touch.

L. Troman, Wine, Women and War

2002

The stewardess walked down the aisle, checking that all seatbelts were fastened for landing, with an immaculate, generalised smile. She did not notice the old woman who dabbed her eyes a few more times than might have been necessary. Beside her, her granddaughter fastened her belt. She placed the in-flight magazine in the pocket on the back of the seat in front of her.

Me Before You

Me Before You After You

After You The Last Letter From Your Lover

The Last Letter From Your Lover Still Me

Still Me Honeymoon in Paris

Honeymoon in Paris Night Music

Night Music The Girl You Left Behind

The Girl You Left Behind Windfallen

Windfallen One Plus One

One Plus One Paris for One and Other Stories

Paris for One and Other Stories The Giver of Stars

The Giver of Stars The Ship of Brides

The Ship of Brides The Peacock Emporium

The Peacock Emporium Silver Bay

Silver Bay The Horse Dancer

The Horse Dancer Peacock Emporium

Peacock Emporium Honeymoon in Paris: A Novella

Honeymoon in Paris: A Novella Ship of Brides

Ship of Brides Paris For One (Quick Reads)

Paris For One (Quick Reads)